As we have learned in our introduction post on NDS.Live, it is being developed with one goal in mind: Enable vehicles to access the most current and precise map data where they need it, when they need it. Nowadays, map data moves from in-car storage to the cloud and to distributed systems like V2X. This means that the relevant data can be processed on high-performance computers with far more power than in-car systems. Vehicles can then consume the data as needed – downloaded or streamed. But of course, they cannot download a full map every few minutes just because the weather has changed. So we need to find a compartmentalized map data structure, breaking the map up into bite-sized chunks that can be streamed quickly and without straining the cellular network.

Now, does this mean map data should be fully online rather than stored in the vehicle? Not at all: We, the NDS Association members, believe that some data is better kept in the vehicle. This way, we ensure those systems that need data at all times are not dependent on a working data connection.

In a nutshell, NDS.Live gives us the best of both worlds: Map data stored in the vehicle enables basic functionalities at all times. This system is complemented by any up-to-date, detailed information the various driver assistance, automated driving or infotainment systems need.

However, the question remains: How do we structure such amazingly complex, highly detailed data? How do we make sure that every point of data is updated as often as needed to ensure it’s reflecting reality but as seldom as possible to save on data transfer?

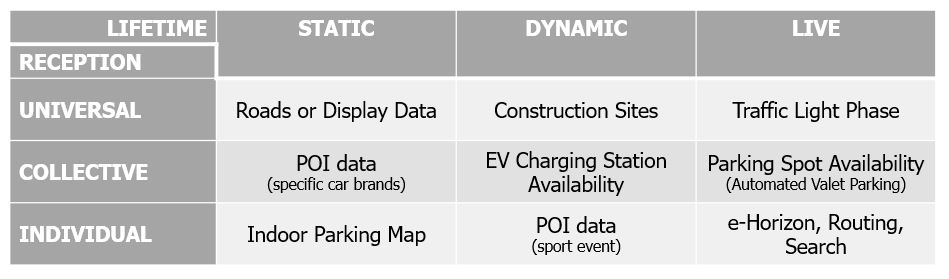

For the NDS.Live map data structure, we considered different requirements concerning the recency of data and different update frequencies for various types of data. Speed limits and warning signs, for example, can be dynamic and change many times per day, and so do parking spaces or EV charging availability. Therefore, this data must be updated with high frequency. Then there is data that changes more often but not daily, such as POI data. A third type of data rarely changes, like the digital terrain model or 3D landmarks, for which a slower update frequency is sufficient.

Data lifetime is one way to categorize map information in an advanced map format. The other one is data reception, which basically means distributing the data on a “need to know”-basis. Let us look how NDS.Live understands these categories:

Lifetime determines when and for how long data can be considered valid and useful. It provides the answer to the question: “How long will the data be valid?” The concept of NDS.Live includes three main lifetime, or “freshness”, types:

The reception aspect answers the question:“Who is this data for?”

NDS.Live defines three types of data for this category:

Although the name “NDS.Live” sounds like the focus is on live data, it will cover all the lifetime and permanence types described here as well. The following table shows data reception and lifetime types for a variety of use cases:

This matrix allows for a very precise categorization of data and for a clean map data structure in NDS.Live. This easy compartmentalization is so important because NDS.Live is not a monolithic database. It is a distributed ecosystem of map data providers, which means that vehicles can pull data from different providers and merge it into a very precise, high-definition model of the world around them.

We will discuss exactly how this is done in our next blog article.

Back to news →